Pınar Kahya: Let me start with a very general question. How do you evaluate the current situation of the world? The Soviet Union collapsed, and the neoliberal capitalism rose towards the end of the 20th century.But where are we currently in the neoliberal globalization phase? You have mentioned about the geopolitical issues, inter-country imbalances, and competition in your article on the “deglobalization” debate in People’s Democracy, June 4th. However, my question is beyond this: what can be said on a global scale about the capitalist functioning, especially the capital-class nexus? Is capitalism different from yesterday and “political” as claimed?

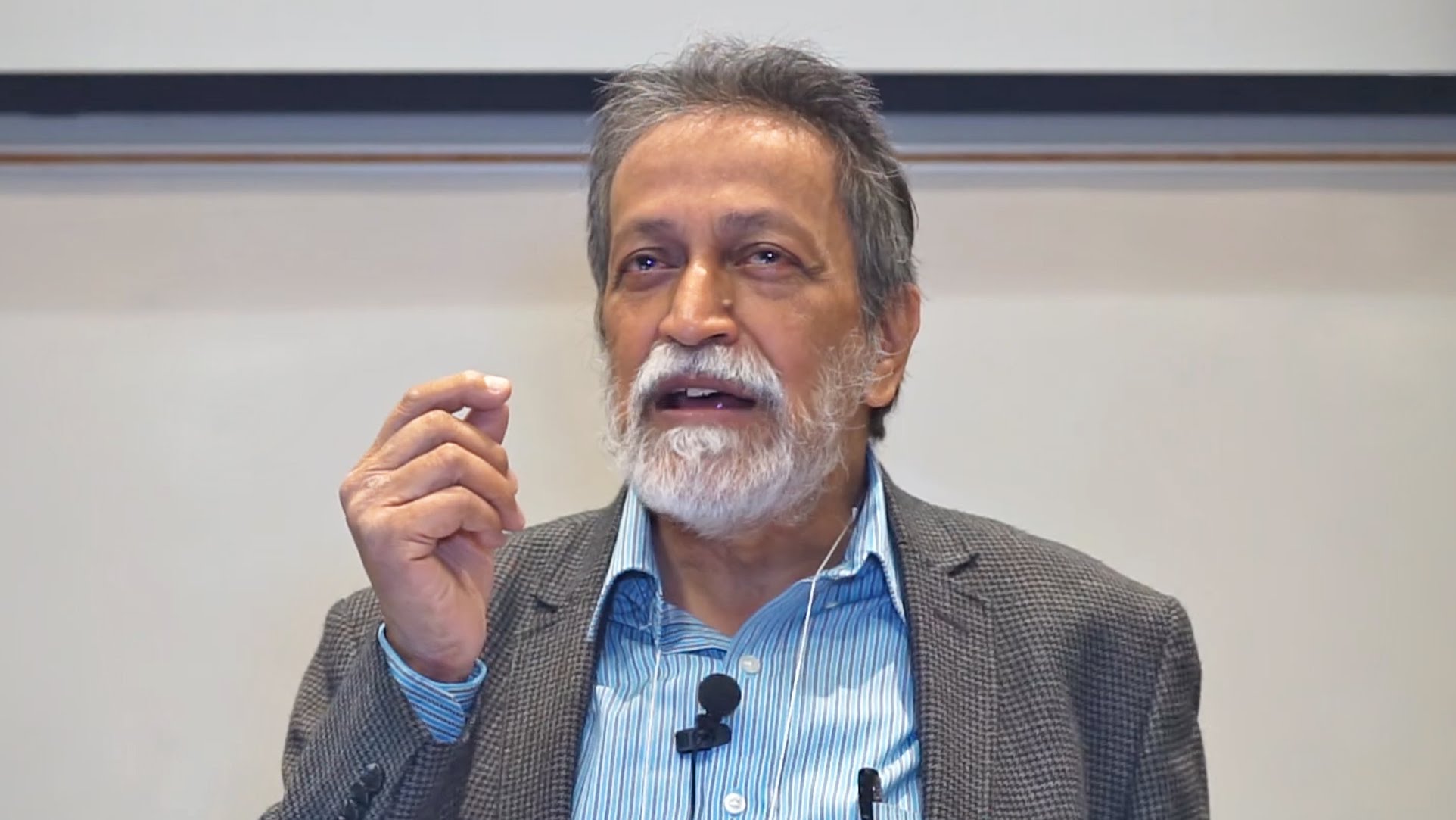

Prabhat Patnaik: I think what is remarkable about the contemporary world is that neoliberal capitalism has really reached a kind of dead end. You mentioned that the last century closed with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the triumph of neoliberal capitalism. What to my mind is the current situation in the world economy is that this triumph of neoliberal capitalism has not only ended, but the system has run into a kind of cul de sac because it has generated an economic crisis which everybody is talking about—a crisis which according to some European writers, has actually seen a decline in the per capita real income in Europe. I’m not sure if this is actually valid, but many members of the European Parliament stated in their speeches to the European Parliament that there has been a decline in European per capita real income.

I’m not talking about the inflation which has been exacerbated by the Ukraine war but began prior to that war, and because of which now interest rates are being raised and a recession may follow. I’m talking even about the pre-2019 capitalism, where you find that the decade ending in 2019 saw a growth rate of the world economy that was lower than for any decade since the Second World War. So, the fact that capitalism is entering into a period of stagnation and there is no obvious end to the stagnation within the rules of the neoliberal game is something which defines today’s reality.

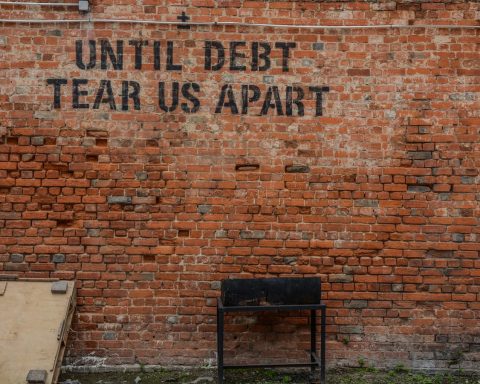

It’s not surprising that the Third World is therefore getting increasingly into a debt crisis. If you cannot have exports growing because the world economy’s growth has slowed down, then in a universe in which countries are more or less open to trade, it becomes very difficult for the Third World countries to meet their current account deficits and to service their debt, which is why they get into debt crises. For instance, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, the latter two of which appeared reasonably well established, and all three of which were actually in the process of transition towards a higher stage of development according to the World Bank’s classification, are now deep in crisis. Pakistan is in crisis. Sri Lanka and Bangladesh are in crisis. Therefore, the end of the boom in the world economy, the emergence of the cul de sac of neoliberal capitalism, which is manifested in a decline in exports of the developing countries is really pushing many of them into crisis.

The advanced countries in this period, particularly the United States, are moving towards greater protectionism. Protectionism, which was originally supposed to be against China for geopolitical reasons, is now going to affect other countries of the Third World as well. The United States itself is moving away from neoliberalism. On the other hand, if the Third World countries get into a debt crisis, they cannot sustain themselves. There will be greater poverty because of austerity measures, and they would have to move out of neoliberalism too. They would have to protect their economies against financial and capital flows, and they’d even have to do controls on trade in order to re-acquire the autonomy of the nation state vis-a-vis globalized finance, so that a certain set of new policies can be introduced which are pro-poor, pro-working people. All these in turn would really require renegotiating the debt with those countries to whom they are currently indebted. They can’t pay back and unless they renegotiate, they would be caught in a trap.

The second part of the question is: is capitalism today different in some sense from capitalism earlier? You know, raw political power in some sense was always the key determinant of the rate of return. Other than the fact that the neoliberal capitalism is in this kind of cul de sac, as I was arguing earlier, capitalism has not changed. How it is going to cope with this situation would determine the nature of the change of neoliberal capitalism. I believe, in the Third World countries, it would mean necessarily a change to regimes in which the working people, that is, workers, peasants and petty producers would become more assertive. New governments would come to power. The new governments would then have to look after the interests of the working people and that in turn would require the autonomy of the state, for which it would have to control capital and trade flows. That would mean opting out of the neoliberal regime. When you opt out of the neoliberal regime, there will be pressure from the advanced countries. To counter that pressure, you would have to further socialize the economy. That could be the beginning of a transition towards an alternative model, even going beyond capitalism.

But when it comes to this question of whether capitalism today is different, not just in terms of investment and rate of return, which is what is being talked about, I think the answer is no for a more fundamental reason. Capitalism has always been imperialist. It was imperialist in the colonial period; it is imperialist even in the current period in the guise of a neoliberal regime; and consequently the claim of capitalism being different runs the risk of suggesting that the First World’s oppression of the Third World has come to an end. We have to be very clear that this is not the case.

My second question is about the authoritarianism debate in general. Comparative politics underlines similarities among different authoritarian regimes in the world. How do you interpret the rise of authoritarian leaders all around the world? You wrote that there are no fascist governments, but there are fascistic tendencies. Can you elaborate on this?

I think when we say authoritarianism, we are actually underestimating the political movement towards fascism that is taking place all over the advanced and backward capitalist world. You see, whenever world capitalism is in a crisis, that becomes an occasion for monopoly capital to form an alliance with fascist elements in order to withstand the challenge to its hegemony that the crisis poses. Typically, this strategy takes the form of shifting the discourse from people’s material living conditions to attacking or creating hatred against an “other”. In other words, isolating an ethnic or religious minority group, and creating hatred among the majority against that minority and thereby shifting the discourse away from the difficulties of living in a crisis situation which affects everybody, majority as well as minority, becomes the typical strategy of monopoly capital. Fascist elements are always there in every modern society, but usually they are a fringe element. Usually, they are a minority element, but they come to the center stage only when they get the support of monopoly capital, in the form of financial support, media support, and so on. Therefore, you have the emergence of a kind of corporate-fascist alliance; calling it authoritarianism is not enough, because authoritarianism does not really suggest either the corporate backing or the fact that it is actually attacking the “other”. Likewise, authoritarianism means repression by using the state organs. But the current regimes do not only use the state organs; they actually use hoodlums and their own groups of vigilantes. They use fascist thugs in order to attack trade unionists, dissenting intellectuals, anyone who disagrees with them, academics, political opposition and civil society groups. So, this is a very specific phenomenon. It is authoritarian, of course. But I think calling it authoritarian alone is not sufficient in bringing out its specificity.

Now, when I say there are no fascist governments but there are fascistic tendencies, what I mean is the following. Contemporary fascism is different from what we had in the 1930s. It is different in two ways. Firstly, you do not yet have concentration camps. You do not yet have complete suppression of the opposition by using fascistic methods. Secondly, that fascism had at least provided some kind of a solution to the problem of capitalist crisis. Japan was the first country to come out of the Great Depression, Germany came out of the Great Depression in 1933. They came out of the Great Depression by military expenditures boosting their aggregate demand, and this was financed by the governments by borrowing, which meant fiscal deficits. Now, in countries of the South certainly, or even elsewhere, you do not have the possibility of larger government expenditure being financed through a larger fiscal deficit, because finance is globalized and hence hegemonic, and global finance is opposed to fiscal deficits being enlarged beyond the limits set in particular countries.

Therefore, this fascism is not capable of resolving the problem of unemployment and at the same time it is not full-fledged fascism in the sense of being complete with concentration camps and death camps. That’s why I call it neofascism. You have to look at this neofascism in the context of today’s capitalist world. But the neofascism nonetheless entails the same tendencies as classical fascism which I mentioned earlier, namely attacking a minority, letting thugs loose on the opposition, and working in the interest of monopoly capital. In Italy, for instance, there was this opposition leader called Matteotti. He made a speech against Mussolini in the parliament. As he sat down, he actually said “I have written my death warrant.” He was found bludgeoned to death in the suburbs of Rome a couple of days later. There is a road in Rome named after Matteotti and also one named after Gramsci. This kind of phenomenon, of bludgeoning opposition members to death, and thereby silencing the opposition is something we have not yet noticed. We may come to that, but we have not yet done so, certainly not in Turkey or in India or even in Italy, because of which I would say that we have fascistic tendencies but adopted by neofascists in power.

In terms of today’s capitalism, what could be said about the financialization process and the role of states in the process? States are restructuring in the process too. Is this process reversible? If it is not, where do we look for alternatives? How?

OK, you see, what is happening now is that we have nation states, and we have globalized finance. The nation state is incapable of retaining its autonomy when the country is exposed to global financial flows.

Are nation states not a part of the process beyond just being passively exposed to it?

It is a part of the process, but it has a character which is different from the nation state in the pre-globalization regime, even though that was also a bourgeois economy. The point is that before neoliberal globalization, nation states appeared to stand above all classes, appeared to be intervening on behalf of diverse classes. Each was a nation state which may be a bourgeois state but appeared to be benign vis-a-vis other classes. On the other hand, after the introduction of the neoliberal regime, the nation state has to act explicitly to promote the interests of globalized finance capital with which the domestic big bourgeoisie is integrated. Therefore, the nation state withdraws whatever support it provided earlier, from the petty production sector, from peasant agriculture, and from the working class. It is much more nakedly in that sense, pro-monopoly capital, pro-globalized finance.

As long as the country remains within this web of financial flows, it becomes very difficult for the country to adopt an autonomous set of policies. Therefore, it becomes very difficult for the country to get out of the whole neoliberal syndrome and, therefore, even from the cul de sac that neoliberalism has introduced into the economy. To get out, the new government must not only impose capital and trade controls, but it must enjoy overwhelmingly the support of the working people, that is the workers, peasants, petty producers even small capital, because the difficulties in the transition will be immense.

What do you think about Lula and Brazilian experience or Syriza in Greece or Podemos in Spain? They are left governments, but, one way or another, they seem to be stuck in neoliberal framework.

There is a difference between Syriza and Podemos on the one hand and Lula on the other. I think the verdict on Lula remains open because we don’t know how far he will go. The verdict on Syriza and Podemos is by now very clear because both (certainly Syriza quite openly) could not break out of this whole neoliberal straitjacket. There are two ways in which it did not seriously attempt to break out. The first is that it made no efforts to demand a renegotiation of the debt. Some debt has to be cancelled, some debt the government might be willing to honor. There was no attempt at an ordering of the debt in this manner to prioritize what should be done immediately. Secondly, it made no attempt to contact China or Russia or any of the countries outside of the Western bloc in order to get some kind of support. Syriza did not even explore any alternatives; and therefore if you don’t explore any alternatives and you remain committed to the rules of the game of the European Union, in that case you cannot pursue any policy other than what the previous governments were pursuing. Because of this Syriza, even though it came to power promising to be different, ended up being the same, which is why the people got quite fed up with Syriza and it lost heavily in the last elections. And I think even the Podemos has gone more or less the same way.

I think within Europe, the left tendencies that had come up have generally been declining, though of course, Mélenchon is still there and it remains to be seen whether he can actually carry forward his agenda. As far as Jeremy Corbyn is concerned, there was a conspiracy within the Labour Party to incapacitate him, which is dreadful. There’s an attempt to even suppress a documentary that shows how Jeremy Corbyn was incapacitated, the conspiracy against Corbyn. Most of leftist groups have to fight not only against global capital, but they also have to fight against domestic capital that is integrated with global capital and even sections of domestic middle classes who have been beneficiaries of the neoliberal regime and certainly don’t want power to pass into the hands of the workers for a more left-wing trajectory of development. So, the transition from neoliberalism is difficult, but the left has to manage this difficult transition.

Has the situation been the same for the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in India?

It has been absolutely the same. The only thing is that now because of the emergence of a neofascist government, within the UPA, within the Congress Party, demands are being raised about people’s issues. It’s very clear that when the neofascists are targeting Muslims, it’s not enough for you to say, “No, Muslims are your brothers”. I mean, of course you must say that but that is not enough. You have to shift the discourse. If you want to shift the discourse, you have to promise people a better world. That’s why in Karnataka, they [the Congress Party] won the election by making some promises which are for improving people’s conditions. If you are going to fight a national election, you have to similarly make promises of an alternative order. It may not be an alternative socialist order, but an alternative order in which the working people are going to be better off. That is the only way you can attract their support.

But if you do that, and if you’re not to betray the working people, then it seems to me that logically you’d be forced into taking steps that really negate the hegemony of global capital and the domestic bourgeoisie. That’s not going to be easy. Being really left wing in today’s world is not an easy job. On the contrary, it’s exceedingly challenging and difficult. But at the same time, there is no alternative to it. You have to prepare the people to make sacrifices and you have to be prepared for all kinds of difficulties.

Many Latin American countries are facing them; so you can see the difficulties. The advanced countries are going to put sanctions against you and sanctions are going to make life difficult. But you have to be prepared for all that. If necessary, some small countries should get together in order to form a minimum sized economy that can withstand sanctions. Large economies like India which are more or less capable of producing all the goods they need other than oil, can actually withstand sanctions better; and they can negotiate, say with a country like Iran which is also under sanctions, for oil supply.

The left will have to work out strategies. I think the coming years are going to see an intense working out of strategies and only if these strategies are worked out and pursued with determination, can mankind get out of the cul-de-sac. Only the left is capable of doing it. Only under left initiative can get mankind out of the cul de sac of neoliberal capitalism. Only the left can work out such a strategy of transcending neoliberalism.

In Greece, they have got rid of Syriza and they have elected a right-wing government, but that right wing government is not going to alleviate people’s distress. What it would do is to go back to neoliberalism. So, it will be back to square one. But if you are serious about getting out of it, you’ll have to be willing to take the challenge head on and, of course, face the difficulties and prepare people for it.

My last question is about India. People wonder what is going on India in general. G-20 presidency, Modi, Hindutva, neoliberal financialization. Can you briefly tell what are the necessary benchmarks of Indian political economy analyses recently?

The neofascist regime as I mentioned earlier, has not yet led to a full-fledged fascist state, because if it had, then I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you like this. So, obviously, we don’t have a full-fledged fascist state, but on the other hand, it’s neofascism using fascist methods to silence its critics. Its tendency is obviously in that direction. Now, every opportunity is actually used to project the leader of this neofascist regime.

One of the very important features of this neofascism everywhere, and particularly in India, which it shares in common with earlier fascism, is the projection of the leader; “eine Volk, eine Reich, eine Führer”. Similarly, everything in India today revolves around the leader. Now India’s assuming G20 Presidency is because it rotates. After all, it had to come to India at some point as India happens to be one of the 20. But this routine development has been turned more into a public relations exercise in order to claim that great things are happening in India, and that the world is looking at India with renewed respect.

Everything, literally everything, is turned into a way of projecting the leader. I don’t think India has any concrete plans about improving the conditions of the world in general, particularly of the Third World. In the context of the current crisis, some attempts such as renegotiating the Intellectual Property Rights Convention, renegotiating the WTO agreement to allow countries greater options, should have been forthcoming. Similarly, imposing capital control without attracting sanctions from the advanced capitalist countries should have been a demand of the Global South. I think India should be pressing in these directions, which are absolutely minimal; but nothing of the sort is happening. At least to my knowledge, India has not made any noises in these directions. But what we have is plenty of pictures and cutouts of the leader.

You and Utsa Patnaik have a huge amount of literature on the nature of capitalism in India. What are the defining features or non-negligible characteristics of capitalism in India for now?

Colonialism created huge labor reserves in countries like India, that is in all colonies and semi-colonies. This was through deindustrialization and through appropriating the surplus from direct colonies without any quid pro quo. That was the beginning of the formation of labor reserves. The increase in the size of labor reserves relative to the labor force is something that came to an end with Independence. The entire period in India before neoliberalism began was a period in which the rate of growth of employment was roughly about 2% per annum. The rate of growth of population was also roughly about 2% per annum. We can assume that the rate of growth of working age population would have been similar. So, what was happening was that the rate of growth of employment more or less matched the rate of growth of the workforce but did not make a dent on the labor reserve that existed earlier; in fact, the labour reserves also continued to grow at the same rate of about 2% per annum. With neoliberalism, what is happening is that the labor reserves are, in fact, once more expanding relatively faster. That’s because the rate of growth of employment has slowed down to less than the rate of growth of the workforce. With trade competition entering the picture in a neoliberal economy, countries are more or less forced to bring about structural-cum-technological change to withstand competition from others.

If there is a small local shop but Amazon is coming and selling vegetables in your home; in that case, many people would go to Amazon; not the poor perhaps, but the middle classes would go to Amazon rather than bother to go and buy from the local shop. Therefore, the local shop keeper loses his customers and becomes unemployed. This raises the relative size of the labour reserves and increases income inequality. As the income inequality increases, you actually find that this process of labour displacement becomes further accentuated.

For all these reasons, the rate of growth of employment slows down. You find that the relative size of the labor reserves once more begins to increase. This is something which gives rise not only to a rise in income inequality but also to a rise in absolute poverty, at least in the sense of nutritional poverty. The proportion of people below the calorie norms that are used for defining poverty, has actually increased quite sharply in the neoliberal period compared to what it was at the beginning.

You have a rise in inequality, a rise in poverty, a rise in the relative size of the labor reserves, and it is this that Utsa and I have been drawing attention to. These are not accepted by many in the economics profession and certainly not by agencies like the World Bank and the IMF. According to them, the inequality has increased but poverty has gone on declining. This is the theme that I wish to challenge on the basis of data which are worked out by Utsa. They show that the proportion of population below certain basic nutritional norms has actually increased quite significantly in the neoliberal period, and matters have actually become worse in the period of neoliberal crisis.

In other words, this worsening was happening in the period of neoliberal ascendancy, but has become even more accentuated in the period of neoliberal crisis. It is this which provides the stimulus to fascism to prevent people from rising up; at the same time, it provides the opportunity to the left and segments of the progressive bourgeoisie to overcome neoliberalism and neofascism by having an agenda that would promise to the people an improvement in condition of their lives.

*Söyleşinin Türkçe tercümesini okumak için lütfen buraya tıklayın.

*This interview, which took place on July 3, 2023 in Bengaluru, India, was first published in Turkish on August 20, 2023. Please click here for the Turkish translation of the interview.